Screenwriting structure can be difficult for the right-brained writer. Before I sort this out, yes, writers must use both the right and left sides of their brains in order to write. When I say “right-brained writer,” I’m talking about someone who tends to be more creative and not always as logical as what might be necessary for a solid command of screenplay structure. If you feel your creativity usually flows first and analysis of your project comes second, you may be a more right-brain dominant screenwriter.

Screenwriting structure can be difficult for the right-brained writer. Before I sort this out, yes, writers must use both the right and left sides of their brains in order to write. When I say “right-brained writer,” I’m talking about someone who tends to be more creative and not always as logical as what might be necessary for a solid command of screenplay structure. If you feel your creativity usually flows first and analysis of your project comes second, you may be a more right-brain dominant screenwriter.

What exactly ARE the right brain and left brain?

The Right Brain is the life of the party inside your head. It’s brilliant, writes scenes that are sometimes miraculously drawn from your subconscious, as well as including brilliant sub-text and theme through inventive ways. It’s so cool, you want to hang out with the Right Brain and discuss all of its great ideas.

For me, the Left Brain is the buzzkill. Even though it’s responsible for giving form to your story, it hides out by the chips and dip and criticizes every good idea you have. It’s super logical, reminding Right Brain why this or that won’t work, or simply whining, “How can you ever make that work?!” This is why the Left Brain doesn’t get invited much to cocktail parties.

Okay, that metaphor probably went too far. But you get the idea. This is the internal struggle I, and many of you I suspect, struggle with in your screenwriting, especially when it comes to structure.

Can you master structure if numbers are the enemy?

When I was a kid, I loved making up stories. I loved creating characters—everything from monsters to everyday families my parents just hadn’t met yet. I did struggle, however, with anything that needed to be quantified—telling time, making change, measurement. To this day, if I have to be somewhere, and it takes forty minutes to get there, I struggle to think backwards to when I need to leave the house. For going out to restaurants, I carry a tip cheat sheet in my wallet, because, hard as I try, no formula, no matter how easy to remember (and my sister has tried them all on me), will I remember the next day. I feel like Drew Barrymore’s “Lucy” in 50 First Dates, where the next day, my mind will be wiped clean, and I’ll forget the formula I memorized the day before.

I’ve seen loved ones grow exhausted, their eyes pleading with me, to just remember how easy it is to work out the percentage of a discounted price in my head. But no. I won’t remember it. And that’s okay. What was that book, I’m Okay / You’re Okay?

In light of this, it should come as no surprise that every time I’ve studied The Seven Story Beats (or is it nine?), dramatic plot points, etc., I struggle with, not what they are, but when they happen, how many pages in, etc. I’ve heard it said that you shouldn’t write to any formula—and I agree!—but that you do need some awareness of structure, so that you can have a tight, well told story in the space of less than two hours.

Noise, noise, noise!

Don’t listen to everyone’s advice.

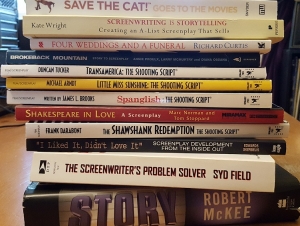

Everyone has their preferred “method” of screenwriting structure. They use that method to sell books, workshops, and some simply share what works for them on YouTube videos. I’ve taken in a lot of different approaches—and like advice, you take what works for you or makes sense, and throw away what doesn’t work for you, or in my case, only complicates my life.

Everyone has their preferred “method” of screenwriting structure. They use that method to sell books, workshops, and some simply share what works for them on YouTube videos. I’ve taken in a lot of different approaches—and like advice, you take what works for you or makes sense, and throw away what doesn’t work for you, or in my case, only complicates my life.

What screenwriting structure REALLY is. . .

Here’s how I think of screenplay structure: Structure isn’t something your audience should ever notice; it’s the underpinnings of the story that propel it forward. It’s what keeps your audience from yawning and saying, “This is getting really slow.” Then they flip the channel or walk out of the theater, and your career plunges off a cliff. You go back to selling tacos at a stand in Minnesota in the dead of winter. (Not that there’s anything wrong with tacos. Or selling them. Or Minnesota.)

How pictures can help you understand structure. . .

I’ve come to realize I’m a visual learner and thinker. Picturing something holds it in my head in a more concrete way than just hearing something, listing it, taking notes, or the repetition of taking notes. Michael Arndt, the screenwriter of Little Miss Sunshine and Toy Story 3, shares a wonderful graphic that helps to illustrate story structure. It goes something like this (apologies to Michael Arndt if I screwed this up). A girl is holding rocket fuel during the set-up, then getting a rocket ship in the second act, then losing that ship at the midpoint, and getting sucked down a trap door at the crisis point. Something like that. It’s a great tool if you have trouble remembering the elements of structure.

Three-Act Structure is easy to remember because there are just three acts to remember. But sometimes, it seems to me that screenplays really have four acts. More on that in another post.

What is the secret formula for screenwriting?

What I see on social media, in books and videos, from writers of every genre is this: You want so much to commit elements of structure to memory, to have at your disposal some winning formula that lets you crank out big hit after big hit.

Let me be the buzzkill now and let you in on a secret no one seems to be able or willing to share: there is no formula. I repeat!!! There IS NO formula. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve watched a video where some self-proclaimed screenwriting guru has declared a certain set of conditions that EVERY well-crafted story seems to include. They’ll share some examples of movies that seem to fall right into place with their “method.” You’ll be like, “Oh, yeah! That really does work!”

Proof that formulas don’t work in screenwriting

Eventually, the guru struggles to contort their method into other, sometimes Oscar-winning films, that don’t include any of the things the guru said would be present.

The mentor character? Sometimes the protagonist has to be her own mentor. Uh huh. You heard me!

Don’t use voiceovers. Really? It seems to work brilliantly in The Shawshank Redemption. There is a key to making a voiceovers work well, which I’ll also cover in another post.

The protagonist must always make an unhealthy choice first. Really? What if it seems perfectly healthy at the time, but something unbeknownst to the character is at work? Hmm?

Never write multiple protagonists. Oh really? What about The Breakfast Club? The Big Chill? Crash?

Beware of gurus using words like “never” and “always.”

My favorite thing is to watch one of these videos, then go off and list some of my favorite films and struggle to figure out this equation they’re supposed to reveal—like the code behind a website. But as often is the case, the films I choose don’t fit the “equation.” Hardly ever.

Having said that, certain elements must be there, for sure. This may sound like a contradiction, but yes, there are some basic things usually present in a good script. You typically have three major acts. And you do have an inciting incident, which truly is necessary to get the story moving. If you don’t, you could be watching a (insert name of a director I don’t want to disparage) film. But he knows who he is. Most of his movies are rambling, never go anywhere, and they’re like watching someone’s boring home movies—two or more hours of “slice of life.” But I won’t name him.

What I’ve decided to do after years of frustration, thousands of notebooks, hundreds of Word and Final Draft files is to come up with something that works for me in the broadest, general terms. Like everything else, the exceptions to the “rules” cause writers to pull out their hair unnecessarily. Remember, nothing fits in a formula, but some basic principles are good to know.

No matter what anyone says, originality IS your friend.

I’m going to use the tired cliché of building a house. You most likely start with cement for your foundation. But the design and progression of that design might not resemble other houses and their building processes at all. Okay, let’s not get in to carpentry’s best practices and all of that. You know what I mean.

I’ve heard it said that studio execs may get nervous if you say your idea is unique. They say this may translate to something unproven, and therefore, the studio won’t want to take a risk on your material. Excuse me? Some of the biggest breakout screenwriters did something fresh and original—or, as many advise a fresh take on a familiar topic. However you want to look at it, remember, rehashing something you think will sell probably won’t get you noticed. Diablo Cody turned teen pregnancy into a quirky comedy with Juno. Now she’s an in-demand screenwriter. Think about that a minute. Is there a topic that you could put a fresh twist on?

Don’t let formulas block your creativity.

You don’t want to say to yourself, “It’s like Rocky but without boxing. So I’m just going to copy the story beats in Rocky and duplicate that in my non-boxing story.” You could, and it might actually work. But I’d prefer to tell my story using my own set of characters and situations to guide the way.

Since the right brain is responsible for making connections with things that don’t typically connect, USE that. Think of a favorite singer, someone iconic, then pretend they’re the villain of your story. Take the premise of a TV commercial and blow it out into what you imagine would be a complete movie about it.

I prefer to think of the right side of my brain as a gift, not something to constantly fight with in order to contain it. The key, I think, is finding a way to use it, then know when to invite the left brain over to the party. Screenwriting, it seems to me, is the often imperfect merging of these two sides. And if you can figure out when it’s best to use the skills of each side, you might actually have it made.

Need help? For screenwriting consultation, visit here.

Renée Lukas is the author of four novels: The Comfortable Shoe Diaries, Hurricane Days, Southern Girl and In Her Eyes (Bella Books). She’s also a screenwriter, an Academy Nicholl Quarterfinalist and a reader for BlueCat Screenwriting Competition.