by Renée J. Lukas

As a struggling screenwriter, you’ve read books and articles, attended seminars and workshops, drawn charts and graphs. . .and you’re still as confused as ever about the craft and business of screenwriting.

As a struggling screenwriter, you’ve read books and articles, attended seminars and workshops, drawn charts and graphs. . .and you’re still as confused as ever about the craft and business of screenwriting.

If you never read another thing about screenwriting, read THIS: the 5 absolute truths about screenwriting that you can take to the bank (I’m pretty sure).

1. Nobody knows anything.

That’s right. No one does, though they all act like they do. I could tell you not to waste years of your life trying to sell a screenplay that everyone says is bad because a) many great scripts that turned into great films were rejected too, and b) if it really is bad, it may still sell anyway.

This may sound funny since I’m dispensing advice here, but don’t listen to all the advice you get. Everyone has an opinion. They’ll tell you never to do x, y, z in a pitch meeting. Then someone else will say you should absolutely do x, y, z. So by the time you’re ready for your first pitch meeting, dressed half-formal / half-casual because you couldn’t make up your mind, you may be struck dumb with your head spinning because you forgot what was “to do” and what was “absolutely never do.” Make eye contact with everyone? Or just one person? Talk a little about myself? Or say nothing at all about myself and dive right in to the project. . .Sweat begins to pour.

The best you can do is be yourself, whether writing or pitching. Take the advice that makes the most sense to you, and let go of all the other noise. Because everyone sounds like an expert, they’ll make you feel silly for pursuing that historical drama: “Studios don’t like period pieces because of the budget.” Oh really? Lots of movies about World War II lately. Dunkirk, anyone?

Ultimately, as with everything else, you’ll have to trust yourself.

2. If you pay money to any website that promises more access to decision makers, it’s like buying a lottery ticket.

Don’t get me wrong. Some writers have actually been signed this way. My experience has been frustrating, at best. I’ve received the best-sounding “passes” ever: clever idea, definitely sellable, but “not in my wheelhouse.” Great. So can I please say thank you for the feedback and ask to be pointed in the direction of someone whose wheelhouse it IS in? But I can’t, because contact information for this person is locked up tighter than a CIA vault. Deflated, I realize there’s nothing I can do to touch base in a normal, businesslike way.

So face facts. Everyone at high levels will assume you’re a stalker if you aren’t already friends with one of their friends. Which brings me to. . .

3. It’s who you know—AND the quality of your work.

I signed with a television producer because he liked my work. Period. I reached out, he liked what he read, that’s it. So sometimes your work gets you in the door. Sometimes, your friend, who’s a friend of a major producer, introduces you to that producer. Sometimes, it all boils down to a shared love of llamas at a llama farm you happen to be visiting at the same time as a producer or agent. In other words, it’s not an exact science. Keep expanding your contacts and keep working hard at your craft, so when the opportunity comes, you’ll be ready.

4. Screenwriting rules are basic, but no one can agree on what they are.

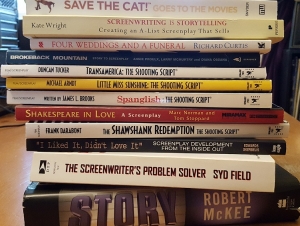

Many will agree to a three-act structure, and that’s where the consensus ends. You have to find out what works for you and best serves your story. If you’re the kind of person who wants a template or some kind of parameters to make you feel comfortable, you probably drew the graph from Syd Field’s book. I prefer to start telling the story first, then panic later when my structure doesn’t work. To hone this skill a little better, I’ve played around with templates, which are sort of like puzzles, to see how many stories can be boiled down that way. If you do this, you’ll most certainly run into exceptions that don’t fit neatly into anything. But if it makes you feel better, try this:

In Act One, there’s an initial question to be answered. By the end of Act One, it’s answered. And the answer is what causes the problems in Act Two. By Act Three, at the climax, a more central question has to be answered.

Here’s an example (spoiler alert): In Something’s Gotta Give, the central, looming question is whether or not Harry will change his ways and stop being a womanizer. The more immediate question is whether or not Erica will fall in love with Harry. She does.

Here’s an example (spoiler alert): In Something’s Gotta Give, the central, looming question is whether or not Harry will change his ways and stop being a womanizer. The more immediate question is whether or not Erica will fall in love with Harry. She does.

By Act Two, her love for him causes great pain and suffering when, after convincing herself she was the one to change him, she catches him with another woman.

In Act Three, at the climax, Harry confesses his love for Erica. He’s even circled the globe to right the wrongs of his past, proving that yes, he will stop being a womanizer, the central question above.

This, of course, is an oversimplification. But sometimes you need to start with the bare bones before you add more meat to your story. (Sorry for the carnivorous metaphor.) But you get the idea.

Plug in your favorite films to see what they have in common and how the structure works in each of them. And keep checking this blog for more tips about structure.

5. You have to love what you’re doing.

If you are truly a screenwriter, there is no immediate gratification. There isn’t always the financial compensation you hope for. There are long hours, and your friends and family will think you’re crazy most of the time. Sometimes the politics of the business will cause a heartbreaking loss just when you think your career has taken off. If you’re still compelled to get up each morning and pound out more scenes on your computer because you can’t NOT do it, then you must go ahead. Remember that hard work and tough odds make the rewards that much sweeter!

Good luck and happy writing!